13:26

News Story

Indigenous people stepping up their opposition to ‘water grab’

Indigenous people are gearing up to fight the next round in a long battle against Southern Nevada’s thirst for other people’s water.

Members of several tribes, including the Navajo and the Southern Shoshoni, met in Las Vegas this week to discuss how to step up their opposition to the massive groundwater pumping and piping project that the Southern Nevada Water Authority (SNWA) has spent nearly three decades trying to develop.

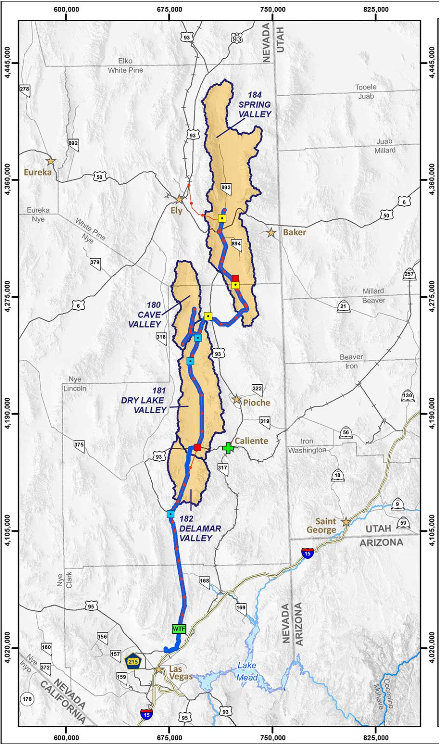

The proposed project would build a 250-mile pipeline to carry 27 million gallons of groundwater each year from rural Eastern Nevada aquifers to Southern Nevada. The project has been described as potentially “the largest interbasin transfer of water in U.S. history.”

Legal and regulatory challenges from environmentalist, ranchers, local governments, and tribes have argued over the years that the pipeline will draw down aquifers beyond their capacity to naturally recharge – that the project effectively amounts to groundwater mining, and will irreparably harm rural communities and natural wetlands where some of Nevada’s rarest and most vulnerable species live.

Last year, a federal district court judge ruled that the Bureau of Land Management failed to show how it would compensate for significant losses to wetlands and wildlife habitat caused by the pipeline, and ordered additional environmental analysis.

While a lot of focus has been placed on how the project will harm rural agricultural livelihoods and more than 200 square miles of habitat for sage grouse, mule deer, elk and pronghorn, tribes feel their interests have received less attention.

The indigenous peoples who will be impacted by the groundwater pumping project include the Koso, Northern Paiutes, Western Shoshone, and the Moapa tribes.

Beverly Harry, a community organizer in Northern Nevada for indigenous communities, believes the pipeline will cause territorial displacement and cultural disruption for tribes.

“It’s apparent that we really need to develop an awareness campaign for the protection of water,” Harry said. “There are a lot of important voices that have to be considered. The underlying issue, before the ranchers and the people who settled here in Nevada, are the indigenous people.”

“We’ve been going through this for the past decade and a half,” said Bronson Mack, a spokesperson for the SNWA. “It has been legally challenged.”

Nevada regulators have granted water rights for the project twice before, only to have those decisions reversed in court.

The Groundwater Development Project, as SNWA calls it, is part of SNWA’s 50-year plan to meet Southern Nevada’s anticipated water needs.

Since the plan was developed in 1989, it has prompted frequent and sometimes bitter clashes between SNWA and opponents. When the economy crashed a decade ago, so did the project’s profile. But as Southern Nevada’s economy and population have rebounded, so has attention to its controversial groundwater pumping plan.

An indigenous committee last week noted that the Clark County Commission is asking Congress to pass a federal lands bill that will allow more development in Southern Nevada – another sign that recovering from the crash also means renewing demand for – and refreshing the fights over – water.

Harry is now helping lead that committee to organize a traditional Native American relay run, a method of carrying messages and important news across long distances. She hopes to use it as a way to get their message across.

The path of the relay run would follow along the proposed pipeline, starting on Oct. 5 and ending Oct. 8, Indigenous Peoples Day.

“We have the opportunity to build an awareness campaign,” Harry said.

Protesting the Dakota Access Pipeline in South Dakota garnered international attention to the indigenous people who carried the movement.

As part of that indigenous resistance, native youths participated in a 2,000-mile relay run from the Standing Rock reservation to Washington, D.C to deliver a letter to the Army Corps of Engineers asking it to deny the Dakota Access Pipeline permission to cross the Missouri River. The Army Corps agreed to reopen study of the pipeline route during the Obama administration, but that decision was effectively countermanded by President Trump.

Still, Harry wants to emulate that spirit of protest here in Nevada by sponsoring ten indigenous runners to take up the task. The hope is that the relay run will raise awareness of the groundwater pumping and piping project, with voices of historically neglected indigenous communities at the center.

“My vision is to look at how the Standing Rock youth have brought an enormous campaign to the protection of water,” Harry said. “What I see is a native runner holding their flag across the desert.”

The next step for SNWA, meantime, is finalizing water rights permits. Otherwise, SNWA will have no water to pump.

Mack says the aquifers are the only water available in the state, and any other option would have to include negotiations and contracts across state lines. According to Mack, seven out of ten Nevadans live in the Las Vegas Valley and economic expansion in Southern Nevada will continue to grow, increasing water demand.

“When you think about the economic activity generated in Southern Nevada it benefits the whole state,” Mack said.

Our stories may be republished online or in print under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. We ask that you edit only for style or to shorten, provide proper attribution and link to our website. AP and Getty images may not be republished. Please see our republishing guidelines for use of any other photos and graphics.