3:44

Commentary

Commentary

Nevada has an affordable housing crisis, but no affordable housing policy

In 1940, the median value of a single-family home in the U.S. was $2,938.

Well, it was 1940. Gas was 18 cents a gallon. You could get a Ford sedan (this was back when Ford still made sedans) for less than $800. A loaf of bread was 8 cents.

Adjusted for inflation, 18 cents for a gallon of gas in 1940 would equal $3.21 today – as it happens, about the same as gas costs today. The $800 that a Ford would have cost you in 1940 is, when adjusted for inflation, equal to $15,000 – not a whole lot less than the price of a plain vanilla Ford Focus today. And the 8 cents one might have spent on a loaf of white bread in 1940 would equal $1.43 today. Clip a coupon and you can get a loaf of Wonder Bread for $1.99 this afternoon. (You won’t. Because it’s Wonder Bread. But still.)

And, $2,938 – the median home value in the U.S. in 1940 – equals an inflation-adjusted $52,371.

For that much money, you could get a nicely appointed Ford Valdez or whatever it is Ford calls the automobiles it still makes.

You cannot, however, buy a house, and certainly not one of median value.

Using Housing & Urban Development data, the Census Bureau’s most recent American Housing Survey estimates the median value of a home in 2015 was $180,000, more than three times inflation-adjusted home values of 1940. The same data sets are only broken out for a handful of states, and Nevada isn’t one of them.

Put another way – and not adjusted for inflation – gas is 18 times more now than in 1940; the Ford costs 22 times as much; bread, 25 times as much.

And the value of a home? Sixty-one times as much.

Why has the relative price of housing skyrocketed so much more dramatically than the price of gas, bread, and cars that Ford doesn’t want to make anymore?

Partly for the same reason that Ford would rather manufacture its Nimitz class of vehicles rather than a Taurus: The more expensive a product is, the more profit for the seller.

KB Homes, one of the largest homebuilders in Nevada and the nation, explains as much in its 2017 annual report. Strong housing price increases in 2016 and 2017 “reflected our strategic focus on positioning our new home communities in attractive, land-constrained locations that feature higher-income buyers” – high-income buyers displaying the latest Ford Brobdingnagian in their new driveway, presumably.

And in Southern Nevada, well, it’s not 2010 anymore. As an industry newsletter reported earlier this year, “Production of all homes – detached and attached – priced under $250k has been nearly eliminated as base prices have shifted into the $350k-$450k range.”

High-income buyers aren’t the only market force that has driven home – and, by extension, housing – prices to increase so much more than other things over the last several decades. The post-war emergence of the 30-year mortgage allowed middle-income Americans to borrow enough money to buy much larger homes than the 900 square-foot, two-bedroom one-bath house that sold for $3,000 in 1940. Now homebuyers, particularly buyers of new homes, prefer houses at least three times that size.

People, well, home-owning ones, anyway, are really quite fond of rising home prices. That’s (one of the reasons) why they don’t want affordable multi-family apartment units in the neighborhood vacant lot currently zoned for a cul-de-sac. It would hurt property values.

A legislative committee chaired by state Sen. Julia Ratti, D-Reno, was formed last year to study possible solutions to Nevada’s crisis in affordable housing, a term typically meant to mean housing that costs no more than 30 percent of a household’s monthly income. At its meeting in May, probably the most consequential proposal presented was a system of transferable tax credits for housing developers. The state grants the tax credit, and the recipient – developers, in this case – can sell the credit on the market. Yes, there is a market for these things. Buyers pay maybe 80 or 90 cents on the dollar for the credits, which they can then use to pay their state tax bills. Tesla has been granted tens of millions of dollars of transferable tax credits, and sold a lot of them to MGM. And instead of paying taxes with money, MGM pays the state in tax credits.

The state can spend money on things like education or mental health services. The state can’t spend tax credits on that. Once tax credits are granted, it is money that the state effectively loses.

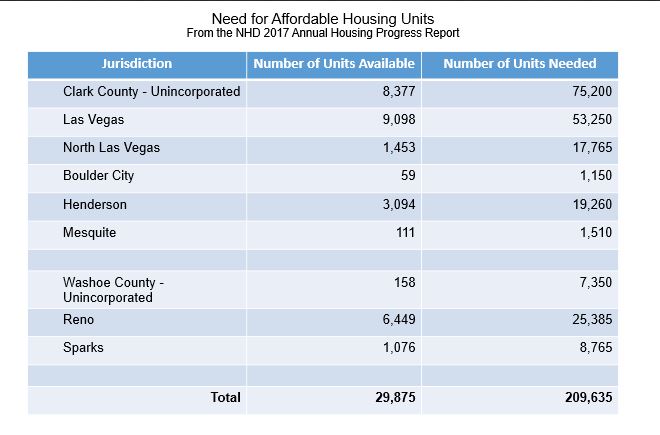

Even if tax credits were a good idea, a debatable proposition at the very least, perhaps even more debatable is whether the $80 million currently envisioned in the program would spur enough supply to meet the enormous demand for affordable housing reflected in the chart at the top of this page.

Tax credits aren’t the only solution under consideration by the committee. There is the customary demand from developers for less fees and regulations. And inclusionary zoning – requiring developers such as to KB build a certain portion of affordable housing when projects in “attractive, land-constrained locations that feature higher-income buyers” are approved – was on the committee’s agenda last week.

Housing in the U.S. is burdened with historically bad and often institutionally racist federal, state and local policy. Society has put a stigma on what little public housing there is, in Nevada and the nation. Funding for low-income housing vouchers is not going to be a priority in the Washington D.C. of Donald Trump and his wildly unqualified Housing and Urban Development Secretary, Ben Carson.

I freely admit that I don’t have an easy solution. But the traditional approach to housing, as reflected in tax credits or relaxed regulations, is to somehow help developers – to somehow help the market forces of supply and demand work their magic and fix the problem.

That chart at the top of this page shows nothing if not a huge demand, just waiting, presumably, for innovative entrepreneurs to swoop in and provide the supply, as per conventional understanding of market forces.

The law of supply and demand has failed to deliver a basic need. But it has successfully delivered a warning: Housing policy based on faith in markets is doomed to fail.

Note: An earlier version of this commentary misstated the estimated market price of transferable tax credits.

Our stories may be republished online or in print under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. We ask that you edit only for style or to shorten, provide proper attribution and link to our website. AP and Getty images may not be republished. Please see our republishing guidelines for use of any other photos and graphics.

Hugh Jackson