5:40

Commentary

“Average hourly earnings have increased by nearly 20% since January 2007,” reads one of the charts presented to state economic forecasters by the Las Vegas Global Economic Alliance (LVGEA) earlier this month.

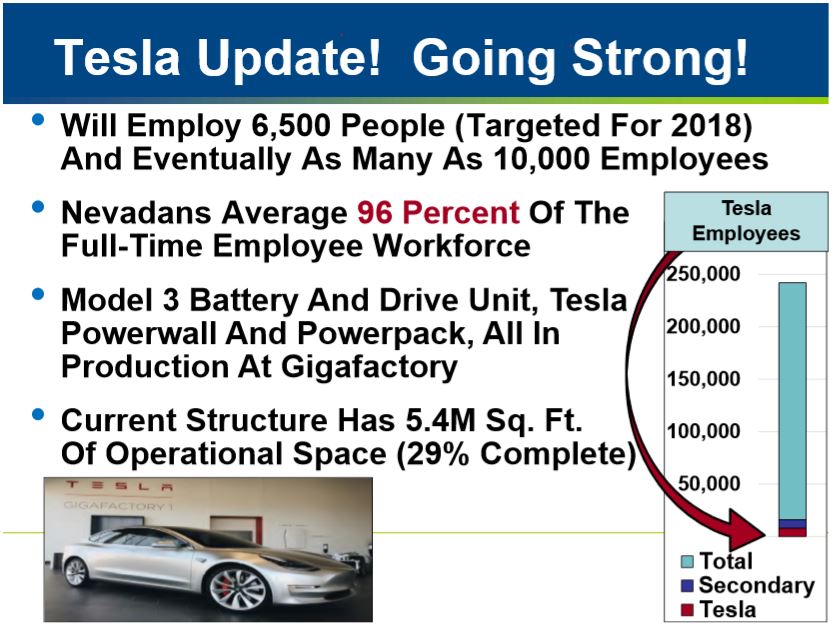

“Tesla Update! Going Strong!” added a graphic presented by the Reno-based Economic Development Authority of Western Nevada (EDAWN). Like LVGEA, EDAWN is part of the state’s multiple initiatives to diversify Nevada’s economy and attract new businesses.

Cheerleading is second-nature to economic development agencies. Every state and city has such organizations. Boosterism is a primary function of all of them.

And that’s fine. Economic development groups are in the business of selling their state or community to prospective new companies. Of course they emphasize the positive.

The danger is when a state or community and its politicians fall too hard for their own sales pitch. An emphasis on new companies, economic diversification, the promising “jobs of tomorrow” and a prospective new economy – pom-pom economics – crowds out discussion of more urgent problems bedeviling the real economy that already exists. Economic policy becomes based not on the need to address structural inequities or troublesome conditions, but on economic development public relations campaigns.

That’s what’s happened in Nevada.

____

Along with presentations from LVGEA and EDAWN, state economic forecasters were also provided a series of charts on Nevada income and wages based on data tracked by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the U.S. Census Bureau, and/or the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). Those charts did not have the splashy layout and exclamation points that accompanied presentations from the economic development groups. And sometimes they tell a very different story.

For instance, that 20 percent increase in average hourly earnings since 2007 touted by LVGEA doesn’t account for inflation. And averages, skewed by extremes on either end, can be an unreliable indicator.

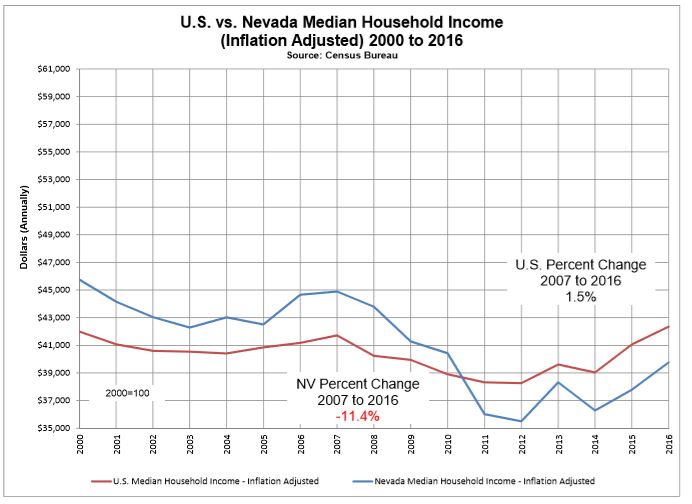

A far more accurate reflection of economic well-being is inflation-adjusted median household income, the income at which half of households have more and half have less.

Real (inflation-adjusted) household income in Nevada dropped from $45,000 before the Great Recession to less than $40,000 as of 2016. Relatively higher wages in construction had a lot to do with the fact that Nevada household income was higher than the U.S. median for so many years. Nevada’s unemployment rate has fallen dramatically since the state persistently had the highest rate in the country early in this decade. But while construction employment has been growing, there are still less than 60 percent as many construction jobs in Nevada as there were before the crash.

The state Department of Employment, Training and Rehabilitation (DETR) forecasts continued growth in construction employment, but not to pre-crash levels, at least not in the foreseeable future. An 11.4 percent drop in real median household income may or may not represent the “new normal.” But it is arguably the most significant indicator of today’s Nevada economy, that is, the economy policymakers tend to ignore while focusing on a different economy that might happen at some indeterminate point in the future.

Then again, the future is now, according to economic development officials.

EDAWN’s enthusiasm is shared by DETR, which forecasts more than 14,000 new Nevada manufacturing jobs through the end of next year. That would increase manufacturing employment in the state to more than 60,000 jobs.

Good.

But DETR also projects that by the end of 2019 Nevada will have 330,000 accommodation and food service jobs, 150,000 retail jobs, and 140,000 health care and social assistance jobs. A good share of those health care and social assistance jobs are comprised of home aides – low-paying, irregularly scheduled jobs with few or no benefits that are projected to be the fastest growing jobs in the nation over the next several years. Low pay, unstable scheduling and no benefits also tend to characterize accommodation and food service and retail jobs, the most common jobs in Nevada.

______

In 2017 the Nevada Legislature passed an increase in the minimum wage and a mandate that employers provide earned sick leave. The governor vetoed both, but their introduction and passage demonstrates that at least some politicians have awakened to at least some of the difficulties working people struggle to cope with in the post-crash economy.

But the economic initiatives that have been approved and implemented in Nevada, typically with broad bi-partisan support, are far sharper reflections of the state’s genuine approach to economic policy: Tax incentives, public subsidies and other giveaways for Tesla, the NFL, the film industry and virtually any and every company that moves to or does some business in the state; a systemic and unchallenged assumption that the utmost priority of education should be “workforce development,” by which the public pays to train Nevadans to get jobs at the companies that get the giveaways; and the reconfiguration, growth and prestige of the state’s sprawling economic development infrastructure itself.

Asked about the economy, candidates for office almost always start with – and rarely get beyond – some testament to the importance of “economic development” and “workforce development.” Wages are too low, and job conditions too unstable or even abusive? That’s why we need to diversify our economy and attract new jobs, and a key part of that is preparing students for those new jobs. That’s what candidates say.

They’re not wrong. Economic diversification is a fine thing. So is having some vision for what the economy could or might look like in the future.

In the meantime, we already have an economy, right now. Yes, it’s better than it was a few years ago. But that’s a low bar. Today’s Nevada economy still leaves far too many people behind.

Policies to improve wages, working conditions, housing, transportation, child care and so much more are another form of economic development, not least because they would strengthen consumer spending that is the lifeblood of most businesses – especially small ones. Those problems, and that form of economic development, are far more urgent priorities than “economic development” as conventionally understood. Or they would be, if those struggling to get by in today’s economy could be heard over all the cheerleading.

Note: All charts are from meeting materials posted for the June 8 meeting of the Nevada Economic Forum.

Our stories may be republished online or in print under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. We ask that you edit only for style or to shorten, provide proper attribution and link to our website. AP and Getty images may not be republished. Please see our republishing guidelines for use of any other photos and graphics.

Hugh Jackson