6:00

News Story

Lawmakers seek expanded study of maternal mortality

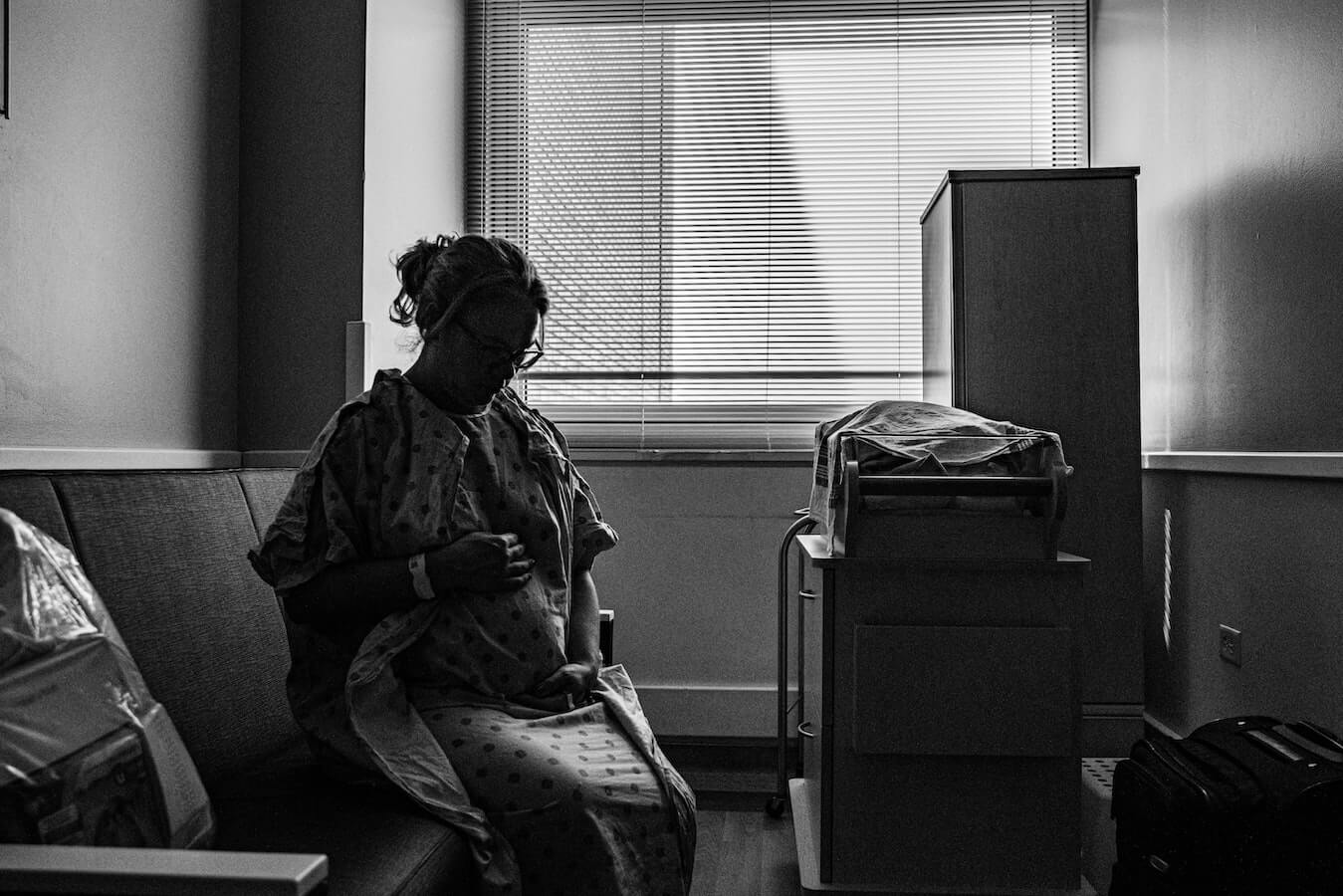

The CDC money is expected to help support the staffing needed to conduct the research and comprehensive death reviews. (Photo by Daryl Wilkerson Jr vis Pexels)

A committee tasked with exploring the reasons why some women are less likely to survive pregnancy has released its initial reports, and data confirms some expected disparities.

Among racial and ethnic groups, Black women had the highest likelihood of a pregnancy-related death, with a ratio of 63 deaths per 100,000 live births, according to 2016-2017 data compiled by Nevada’s Maternal Mortality Review Committee. Black women represented 33% of all pregnancy-related deaths but only 12% of live births.

Disparities aren’t limited to ethnicity and race. Maternal age also plays a significant factor. With a ratio of 85 deaths per 100,000 live births, women aged 40 or older were more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than younger women. The pregnancy-related death ratio for women 35 to 39 was about half that of women 40 and up, and the ratio for women aged 20 to 29 was less than a quarter of the ratio for the oldest birthing women.

A third of pregnancy-related deaths occurred among women aged 35 and older.

Analyzed together, Black women between the ages of 25 and 34 had the highest likelihood of dying from a pregnancy-related cause; their ratio was 104 deaths per 100,000 live births.

The newly compiled data from Nevada aligns with national statistics, which have found that Black, native and Asian and Pacific Islander women have higher likelihoods of dying as a result of pregnancy or pregnancy-related medical issues. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention puts the pregnancy-related death ratio for Black women nationally at 41.7 deaths per 100,000 live births.

The pregnancy-related death ratio for non-Hispanic white women between 2014 and 2017 was 13.4 deaths per 100,000 live births nationally. In Nevada, the pregnancy-related death ratio for non-Hispanic white women in 2016-2017 was 18.4 deaths per 100,000 live births.

When lawmakers rushed to create a statewide Maternal Mortality Review Committee during the 2019 legislative session, they knew the national trends and hoped a deeper dive into the data might shed light on how the state can improve maternal health. Pieces of that picture are starting to form with the December release of two reports from the committee — one on maternal mortality and one on severe maternal morbidity.

The issue got renewed legislative attention last month during the first committee hearing for Assembly Bill 119, which revises the duties of the committee to explicitly mention reviewing disparities among persons of color, geographic region and age. That focus was understood to be a priority, but not explicitly mentioned, during the 2019 bill to create the committee.

Assemblywoman Clara Thomas (D-Clark) is the lead AB119 sponsor, however a bipartisan group of 17 fellow lawmakers — all female — from both chambers have signed on as primary or cosponsors.

That includes Assemblywoman Robin Titus (R-Wellington), a medical doctor in rural Nevada, who told the committee she was happy to sign onto the bill.

“It falls in line with the push to make sure that we can fix any disparities,” she said. “How do we fix them if we don’t know where they are?”

Beyond numbers

In support of AB119, Erika Washington, a member of the Maternal Mortality Review Committee, submitted a letter noting that the committee lacked information on the living circumstances of those who died. For example, knowing what community support or resources were used or were available to the person who died could help shed light on the overarching issue of maternal health.

“Also, having interviews or notes from the family on their home life and living situation, which could also be a factor in poor outcomes, would help us gather a more well-rounded view of their circumstances,” wrote Washington, who is also the executive director of Make It Work Nevada. “Only having notes from medical staff will never give us an opportunity to know if discrimination or bias was a factor in their death.”

That sort of formalized information could amplify the stories of women of color who’ve shared their personal experiences with medical professionals.

Assemblywoman Thomas’ 36-year-old daughter, Edina Flaathen, spoke during the committee hearing last month about her own pregnancy-related medical scare in 2008. She recalled being ill throughout her first pregnancy but having her doctor dismiss her symptoms whenever she asked about them.

“He was an (obstetrician) and went to medical school,” said Flaathen, “so I just listened.”

Then, two weeks before her due date, Flaathen was seen by a nurse practitioner because her obstetrician was on vacation. She brought up the same symptoms she’d previously mentioned, but this time the nurse practitioner ordered blood work and a urine test.

“While seeing someone new worried me, she became one of my biggest blessings,” added Flaathen.

The next day, the expectant mother received a phone call informing her she had preeclampsia and needed to get to the hospital immediately. Flaathen would go on to have three more children, one of their births involving a serious medical scare wherein Flaathen’s uterus ruptured, resulting in her losing over two liters of blood and needing a blood transfusion.

“I am thankful to the doctors who didn’t push me aside,” said Flaathen.

Not everyone is as lucky.

“It’s sad to say that my daughter is not the only one,” says Thomas. “She’s one in thousands that have experienced that — medical professionals who don’t take complaints or concerns seriously.”

Analysts have found that severe maternal morbidity — that is, potentially life-threatening maternal complications — is significantly tied with race and ethnicity, maternal age, maternal education and health insurance status.

Black women accounted for 14.7% of live deliveries but 21.7% of severe maternal morbidity cases, according to 2019 data compiled by the state. Similarly, Asian Pacific Islander women accounted for 9.4% of live deliveries but 12.6% of severe maternal morbidity.

Non-Hispanic white women accounted for 36.4% of live births but 26.6% of severe maternal mortality.

Future research areas

AB119 as introduced also included language to expand the scope of the maternal mortality review committee to include reviews of preventable infant deaths, but that provision is expected to be removed because it’s outside the normal scope of a maternal mortality review committee. Dr. Titus cautioned that entering into infant mortality review will require significant thought and setting of parameters, given the types of medical issues involved.

Thomas says setting up a fetal infant mortality review committee will be proposed during a future legislative session. Currently, no such statewide committee exists and reviews are conducted only at the county or regional level.

Our stories may be republished online or in print under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. We ask that you edit only for style or to shorten, provide proper attribution and link to our website. AP and Getty images may not be republished. Please see our republishing guidelines for use of any other photos and graphics.