7:16

News Story

Wrong Side of the Tracks: LV redevelopment misses Westside

When Carolyn Goodman first ran for mayor of Las Vegas in 2011, she vowed to continue the downtown revitalization sparked by her husband, Oscar, who preceded his wife in office.

Goodman has kept her promise, shepherding $187 million in city investment in redevelopment projects, $163.6 million of it downtown, while other areas of the city languish.

The city has invested only $22 million in the blighted Westside, a predominantly African American neighborhood that lacks basic necessities such as grocery stores.

“The Redevelopment Agency, when it was created in 1986, was created for the underserved areas such as the Westside,” says Katherine Duncan, president of the Ward 5 Chamber of Commerce. “Since we aren’t on the same side of the railroad tracks as downtown, the money has not trickled down. Trickle-down doesn’t get to us. It sounds good in theory, but it’s not working.”

Mayor Goodman, who is running for a third term, declined to be interviewed for this story.

The Redevelopment Agency’s purpose, according to the city’s website, is “to revitalize downtown Las Vegas and the surrounding aging commercial districts. The RDA works with developers, property owners and the community to recruit businesses, create new jobs, eliminate blight and diversify our economy.”

Incentives for development come in a variety of forms, including property tax forgiveness, which can amount to tens of millions of dollars over a span of years.

Revenue generated via higher property values funds the subsidies to developers.

The city has two redevelopment areas. The first — comprised of about 4,000 acres – includes downtown Las Vegas and the Westside. The second is about 1,000 acres and includes areas north of Sahara, west of Maryland Parkway, and the medical district on Charleston.

“The Redevelopment Areas are chosen because they meet requirements of a ‘blight’ definition per state law,” says City of Las Vegas spokesman Jace Radke. “Once the overall areas are chosen, the Redevelopment Agency can then invest anywhere within the Redevelopment Area for projects.”

The Jewel of the Desert

A 61-acre abandoned railroad yard west of downtown, dubbed the Jewel of the Desert by Oscar Goodman and later known as Symphony Park, has benefited the most from the city’s largesse,

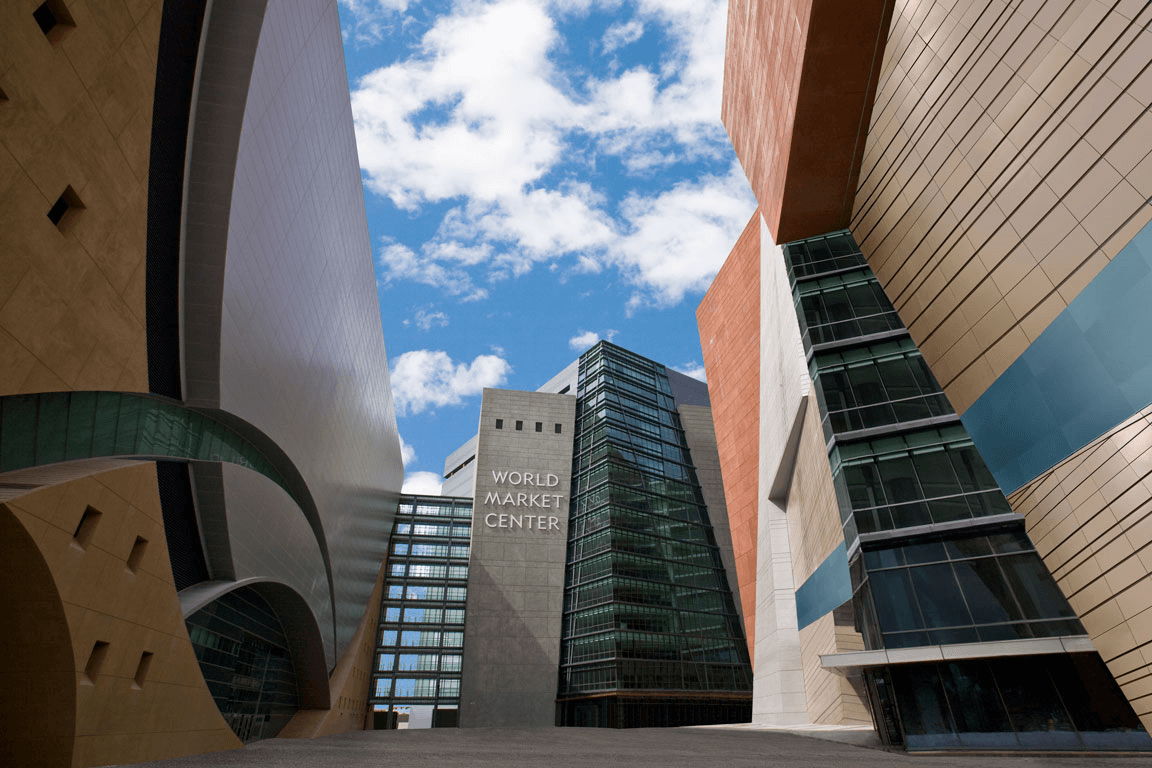

Most recently, in April of 2018, the city contributed $30 million of a $76 million expansion of the World Market Center. It also footed the entire $35 million bill for the Symphony Park Garage.

In 2012, the city contributed land and financing worth $73 million, almost a quarter of the cost of the $310 million Smith Center for the Performing Arts.

The heart of downtown has benefited from redevelopment, too. Online retail giant Zappos got a $7.7 million discount from the city when the company purchased City Hall in 2012, the Downtown Grand Hotel got a $3 million infusion in 2013, and Oscar Goodman’s pet project, the Mob Museum, which was built in part with $12 million money from the city, received an influx of $2.7 million from gap financing obtained via the redevelopment agency.

The other side of the tracks

The predominantly African American “Westside” enjoyed about $23 million in redevelopment efforts — with $12 million of that going to one project — the historic Westside School, the first racially integrated school in Las Vegas, which now houses a radio station and provides office space for local businesses.

The city pitched in $6.2 million for the Adeline Kline Barlow Senior Apartments on the Westside and about $2.7 million in gap financing for the $9.1 million Visions of Greatness Center for the Blind.

But Duncan complains the Redevelopment Agency’s mission was intended to extend beyond the creation of new properties to include new jobs, construction and permanent.

“When the agency was first created, it had a goal of providing employment on every project that got one dollar of funds,” she says. “Fifty-one percent would be people who lived in the redevelopment area with a special outreach to women, blacks, veterans, and protected classes.”

Redevelopment flourished while the employment requirement got “glossed over,” says Duncan, largely for lack of a trained workforce.

“We believe training was our biggest obstacle. Where does a person who is 16 years-old go to learn how to work construction? Where does a woman go to get the skills she needs to go to work in the redevelopment agency area?” Duncan asks. “They thought if they gave a black-owned business a contract, they would have black workers, which is faulty thinking. They all have to pull from the same trade unions.”

Efforts to provide pre-apprentice training on the Westside never got off the ground, says Duncan.

“The city was never able to reach the fifty-one percent level, and instead of pushing the developers who were getting the money, they dropped the requirement to 15 percent.”

City of Las Vegas policy, revised in 2014, calls for 15 percent of contractors, subcontractors, vendors and suppliers to be “bona fide residents of the area.”

“The last big check went to the World Market Center,” says Duncan. “So I went there and asked how we can get people who live in the Redevelopment Area to work. They said exhibitors come in from out of town and bring their own people, so there’s no opportunity for people to work.”

The policy also sets 15 percent as an “aspirational goal” for participation by businesses owned by minorities, women, or veterans.

“We challenged that. ‘Why are you continuing to give this money to these developers when they can’t reach their goals?’ We were in a quandary as to how developers could receive the money when there was no recourse,” says Duncan.

Duncan says it’s up to the city, trade unions and the public school system to help developers reach employment goals by providing training opportunities for those who can’t afford trade schools.

“Were asking for a training facility to be established in our area that would prepare for jobs in all areas of the hospitality industry,” says Duncan.

Duncan and others say Ward 5 representatives on the city council have done little to advance redevelopment on the Westside.

“Our last one was convicted of fraud,” says Duncan, referring to Ricki Barlow, who pleaded guilty to using campaign funds for personal use. “Our current councilman is running for reelection.”

Las Vegas Councilman Cedric Crear, whose Ward 5 encompasses much of the Westside, won a special election to fill Barlow’s vacancy last year. Crear initially agreed to be interviewed for this story then inexplicably backed out.

“We haven’t put a proposal on this desk and he hasn’t come to us with one,” says Duncan. “He says he has one called ‘Ward Five Works’ that he’s going to be rolling out soon. We’re patiently waiting to see how the Ward Five program works.”

The missing ingredient — heads in beds

The remainder of redevelopment investment during Carolyn Goodman’s tenure as mayor — about $1.2 million — went to a senior housing project in Ward Three, which encompasses much of east Las Vegas.

But housing is a rarity on the city’s redevelopment agenda.

Nevada’s Community Redevelopment Law, which governs redevelopment agencies, says “a generally inadequate supply of decent, safe and sanitary housing available to low-income households threatens the accomplishment of the primary purposes of the Community Redevelopment Law, including, without limitation, creating new employment opportunities, attracting new private investments of money in the area and creating physical, economic, social and environmental conditions to remove and prevent the recurrence of blight.”

Despite the statement of public policy, city council members, who also sit as the redevelopment agency, have not prioritized housing.

“We have a lot of bars, llamas, and statues. We don’t have the housing stock,” says developer Arnold Stalk.

“You can’t have redevelopment without housing. It doesn’t work,” says Stalk, who has built half a dozen Veteran Village campuses with private grants. The City of Las Vegas pitched in on one, he says.

“KB Homes has an urban townhouse. It’s been very successful in other areas. But you have to make it attractive to developers, and that doesn’t mean redevelopment money.”

Heavy on the incentives, please.

Stalk says the city’s grueling approval process leaves developers sitting on a piece of property for four to six months, with no means to pay for it while in the approval process.

“We also have a suburban density,” says Stalk. “The City needs to increase density via a bonus program. Right now, they consider 14 to 16 units an acre to be high density.”

High-density mid-rises in other locales can include as many as 40 units per acre.

“Developers are not going to build housing without incentives,” says Stalk. “Relax the water district fees. The sewer connection fees are off the charts here. Add them to the mortgage but make them pay when the project is sold.”

Critics contend redevelopment agencies put government in the position of picking winners and losers. They also say the diversion of taxes siphons money from schools and public services, resulting in a greater burden on taxpayers.

Maryland Parkway: The Next Frontier?

On Tuesday, Clark County Commissioner Tick Segerblom is expected to propose the resurrection of the county’s redevelopment agency, abandoned a decade ago.

Segerblom, an early critic of the taxpayer financed Raiders football stadium, says redevelopment and the stadium handout are vastly different.

“The stadium is actual taxpayer money going to one project. Redevelopment uses tax abatement to incentivize developers to come in and build where they couldn’t afford to otherwise,” he says. “Redevelopment benefits the entire neighborhood, not one project.”

Segerblom says he hopes to see the County spruce up the area near Sahara and Maryland Parkway, including the Commercial Center. He’s also hoping to revitalize Maryland Parkway near UNLV. If successful, he intends to attract developers of low-income housing, affordable housing, and fund housing for the homeless.

REDEVELOPMENT PROJECTS BY AREA DURING MAYOR CAROLYN GOODMAN’S 8-YEAR TENURE:

[table id=13 /] [table id=17 /] [table id=18 /]Our stories may be republished online or in print under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. We ask that you edit only for style or to shorten, provide proper attribution and link to our website. AP and Getty images may not be republished. Please see our republishing guidelines for use of any other photos and graphics.