5:00

News Story

Washoe County School District Superintendent Traci Davis knows there are people who wish she would stop talking about equity.

But she isn’t going to.

“I tend to play the equity card more,” she says. “Some people want to say, ‘Oh, she’s doing it because she’s black.’ No. I’m doing it because it’s right.”

Davis is WCSD’s first black superintendent. She is the second woman to hold the position; Mary Nebgen did from 1990 to 1998. For comparison, Clark County School District has had two black men — Claude Perkins and Dwight Jones — and zero women in its top role.

WCSD is Nevada’s second largest district, behind the massive CCSD. It encompasses 104 schools and 63,194 students. Like CCSD, it is classified as a minority-majority district, meaning the various minority populations together make up more than 50 percent of the overall student population.

Davis has made inclusion “of all students” a hallmark of her tenure, which she began as interim superintendent in the fall of 2014 and officially the following summer.

In June, the school board voted 5-2 to offer her a new two-year contract. That decision was not without controversy, as Davis essentially took a pay cut to keep her job — prompting some local education advocates to wonder whether a white male would have been asked to do the same.

Regardless of the politics going on at the board level, Davis plans on using the next two years to continue the district’s equity efforts. An equity task force will be exploring implicit and systemic barriers that lead to inequities within the district. One example: Looking at the demographics of Gifted and Talented Education (GATE) programs to see whether minority students are being left out despite performing the same academically. Another example: Looking at the relationship between minority students and individualized education plans (IEPs). IEPs are federally mandated accommodations for students who have a learning disability. Research suggests mischaracterization — meaning being told you need an IEP when you don’t, or not having your learning disability identified — is a greater problem among minority students.

Growing research in the world of equity and education has identified areas like these where subconscious decisions and the internal biases of educators and administrators — rather than outright racism or discrimination — leads to stark long-lasting differences in educational experiences over a lifetime.

“What are the solutions that we’re going to (implement) to make sure this doesn’t happen again,” says Davis.

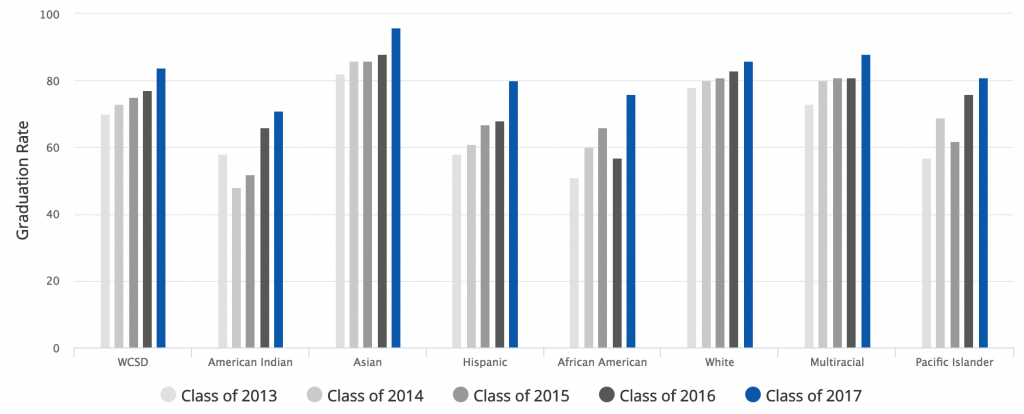

WCSD has already seen gains when it comes to closing what’s called “the achievement gap” — the disparities in performance between different demographics of students. The district’s overall graduation rate for the Class of 2013 was 70 percent but varied dramatically by race and ethnicity: 78 percent for white students, 58 percent for Hispanic students, and 51 percent for black students. For the Class of 2017, the disparity is still there but closing: 84 percent overall, 86 percent for white students, 80 percent for Hispanic students and 76 percent for black students.

If you look at graduation by other measures, the closing of the achievement gap is even more pronounced. In 2013, the graduation rate for students with IEPs was 27 percent. In 2017, it was 59 percent. Similarly, the graduation rate of English Language Learner (ELL) students jumped from 19 percent to 67 percent in that same time frame.

“We’re getting down to single-digit gaps,” says Davis. “We are taking care of all kids.”

WCSD Graduation Rate 2013-2017 by Race/Ethnicity

In addition to looking at what codified barriers might exist within the district and its schools, Davis also hopes to continue to foster cultural competency among administrators, educators and support staff. The racial and ethnic makeup of teachers both in Washoe County and across the nation doesn’t match the makeup of students in classrooms.

There’s nothing wrong with that, says Davis, so long as you have a strategy to make sure that everyone recognizes those differences and bridges the gaps.

“It’s that implicit bias,” she says. “All of us carry it. I have some. I have to work on them. It’s not always race or poverty. We all carry something.”

Davis stresses that equity efforts aren’t just about skin tone. Family income and poverty is a huge barrier to education. She also notes the district’s progressive policy toward transgender inclusion and efforts to make sure all students with learning disabilities are getting the accommodations they need.

“We cannot forget when we look at equity framework that it’s not just about race. It’s also about sexual identity, about religion… It’s very broad.”

In that regard, too, WCSD has been at the forefront. Trustees passed a policy protecting transgender students back in 2015. It took until last week for CCSD to narrowly pass its gender-diverse policy.

This week, the Washoe board of trustees will discuss their legislative priorities for the upcoming 2019 session. It’s likely the funding formula will be discussed. Nevada is frequently found at the bottom of nationwide rankings when it comes to per-pupil spending.

Funding for schools is a complicated topic, and Davis has seen the issue firsthand from a variety of angles. A native of Southern Nevada, Davis spent 16 years in CCSD before relocating to Washoe County for the job of deputy superintendent of WCSD. She began as an elementary school teacher in a Title-1 school. Title 1 is the federal designation given to public schools located in low-income neighborhoods. It opens the door for federal funding. From there, Davis moved to a school that didn’t qualify as Title 1 but was not particularly affluent. After that, she was assigned as a principal of an affluent school in Summerlin.

“What I learned from my experience was that the schools that struggle the most are in the middle. They don’t get Title-1 funding, but the (parent teacher associations) aren’t raising a million dollars for them.”

Davis says additional funding isn’t the silver bullet that fixes all of Nevada’s educational problems — but it is one factor. Different schools have different needs and sometimes those needs require additional funds, she says.

“We will be working hard to address those needs,” she adds.

Our stories may be republished online or in print under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. We ask that you edit only for style or to shorten, provide proper attribution and link to our website. AP and Getty images may not be republished. Please see our republishing guidelines for use of any other photos and graphics.