If a teenage girl in Nevada was convicted as an adult, the options for housing her in a correctional facility would be segregation or sending her out of state.

“There is nowhere in the department of corrections for them to live,” says Holly Welborn, the policy director of the ACLU of Nevada. “This is an issue that needs to be fixed immediately.”

Nevada is facing a crisis when it comes to housing teenagers who are convicted as adults.

Recently, the ACLU pointed out several concerns to the Legislative Committee on Child Welfare and Juvenile Justice. Overall, the ACLU and the Nevada Department of Corrections are on the same page when it comes to the challenges of housing youth offenders in adult facilities.

“We are looking at the same issues,” says Harold Wickam, deputy director of department of corrections. “We don’t have the resources for funding the best practices and evidence-based programs that would help our youth.”

One of the items addressed was the living situations for girls, something that needs immediate action according to the ACLU. There are at least two juvenile girls waiting for sentencing that potentially could have no facility to go to, according to its report.

“We just do not have the facility for females,” Wickham says. “We could house them (at the Florence McClure Women’s Correctional Center), and we do have a plan if that comes to fruition. However, it would certainly mean isolating the individual.”

He adds between the design of the women’s prison and the Prison Rape Elimination Act, which puts in standards to make sure youth offenders never engage adults, segregation would be the only possibility.

In addition to the lack of housing options for girls, the ACLU also looked at the conditions of how boys live in adult facilities.

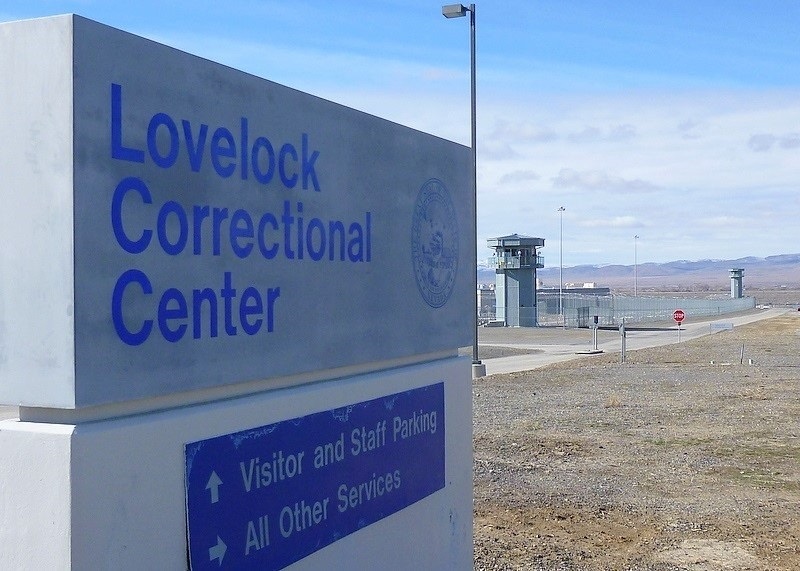

Currently, there are 16 youth offenders housed at Lovelock Correctional Center, an adult facility that garnered national attention when O.J. Simpson was housed there. All are 16 and 17 years old and have sentences anywhere from 12 months to a maximum of 50 years.

Some of the concerns addressed by the ACLU included inadequate access to physical activity and insufficient educational opportunities.

Welborn says the teens have an hour of in-person educational instruction per day and complete the remainder of their lessons on tablets through pre-recorded videos. They can complete classes to obtain a GED, but she says it should go beyond this standard.

“The majority of them are going to be leaving (prison) at some point,” she adds. “Best practices would be preparing them for something more (than a GED).”

That would include vocational training or access to college courses.

“Most of them will re-enter society, but we’re not preparing them for that,” Welborn says.

Additionally, there are only 20 beds in the unit. When the correctional center goes beyond that capacity, which happened earlier this year, boys are housed in the infirmary.

Lovelock became the primary facility to house youth offenders in 2013.

“Our population has been as low as nine and as high as 23,” Renee Baker, the warden of Lovelock Correctional Center, said during the committee hearing.

Again, the Prison Rape Elimination Act made housing the boys at the facility a logistical issue, especially considering about 50 percent of the adult population at Lovelock are there on sex offenses.

“We agree that PREA is needed, and we support it,” Baker adds. “It just has created a lot of challenges.”

While obstacles have increased, there hasn’t been any additional funding allocated to address challenges such as lack of staffing.

Baker adds another obstacle is if youth offenders get into fights, they still must remain in the same unit. And since there is just one unit, there is no way to separate the incarcerated – less dangerous from more dangerous, for instance.

It’s not just living conditions that could impact rehabilitation of youth offenders. The majority of the teenagers housed in Lovelock are from Clark County, a seven-hour drive away, meaning it’s hard to stay connected with families.

“That has a huge impact on the formative years of these kids,” Welborn adds. “They have to have contact with families in order to maintain connections with the outside world.”

The Department of Corrections has established video visitations so families can stay in contact with offenders.

While the ACLU wants to improve standards, they are working toward a larger goal.

“We believe in a complete abolition of confining youth to adult facilities as a whole,” Welborn says.

Statistics show that youth housed in adult facilities are 34 percent more likely to recidivate, she adds.

“It also has impact on their emotional and mental health,” Welborn says.

While some states like Oregon and Washington have addressed the way correctional facilities house youth offenders, Nevada currently isn’t one of them.

In previous legislative sessions, there have been bills restricting the practice, but those never advanced.

Our stories may be republished online or in print under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. We ask that you edit only for style or to shorten, provide proper attribution and link to our website. AP and Getty images may not be republished. Please see our republishing guidelines for use of any other photos and graphics.